Reflections on the Stock Market and My Career

As the Dow Jones Industrial Average reached 40,000 on May 16, 2024, I found myself reflecting on my career and what I’ve witnessed in the U.S. stock market over the last twenty plus years.

Note: The “Dow” or Dow Jones Industrial Average is an index comprised of 30 of the largest companies in the United States stock market (such as McDonalds, Apple, and 3M).

As one of the oldest market indices, the “Dow” is often used as a proxy for how the stock market is performing.

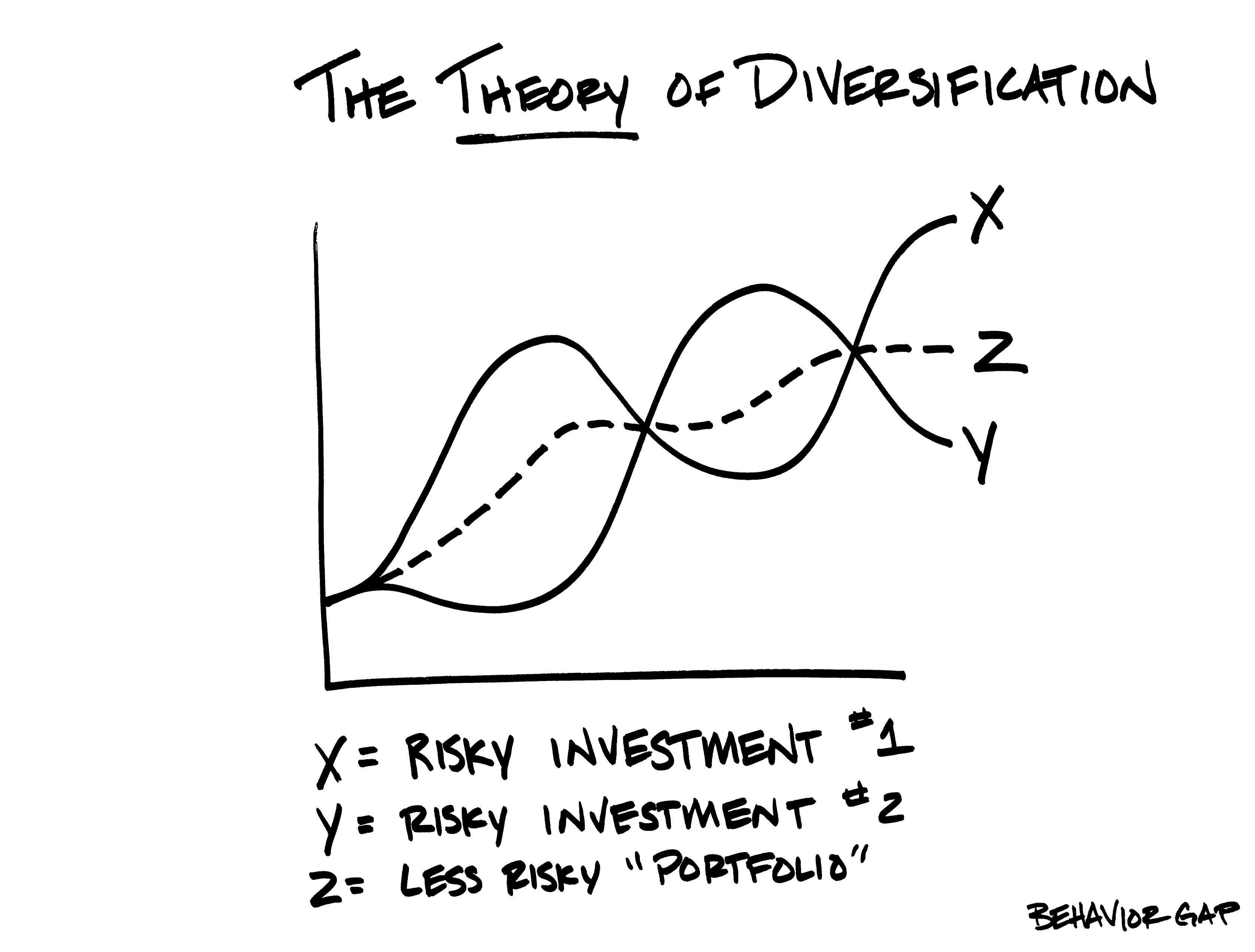

While we believe broad diversification is prudent for investors (and that’s a whole topic itself), I’ll be focusing on the U.S. stock market here.

I began my career at Piper Jaffray in early 2000. I had just finished an MBA from the University of St. Thomas and the investment world intrigued me. Over the last several years, the markets had gone through an explosive rally, driven by the promise of the internet. Technologies were seeing their stock prices skyrocket and it seemed like everybody was jumping on board. What an exciting time to start a career in the financial world!

In one of my prior blogs entitled “Would you have fired Warren Buffett?” I discussed how Buffett underperformed during this time with some investors questioning if he was too old fashioned. Some went so far as to fire him as their investment manager.

Unfortunately, my hiring coincided with the end of the party. In what’s become known as the “tech bubble,” stocks cratered and the tech-focused NASDAQ index fell 78%. That was my first lesson in the risk of failing to diversify and chasing past returns. When a certain investment or sector gets hot, I’ve seen that play repeat itself over the years in things like individual stocks, real estate, and cryptocurrency.